Its history since its origin in 1973

1973 California

In 1973, many of us were travelling on the go in search of inspiring places. Passing through the city of Victoria at the other end of Canada, I went to Huntingdon Beach a few kilometres south of Los Angeles.

I stayed there for a few weeks and experienced a culture, food, a way of living and experiencing the world at the antipodes of our few acres of snow in Quebec.

The narrow strip of sand bordering the Pacific at the edge of Huntingdon Beach stretched from north to south to infinity. During my stay I attended an arts festival that had nothing to envy to what I had seen previously at the Fisherman’s Warf in the prestigious city of San Francisco.

Facilitated by a material ease inaccessible in Quebec, I saw the mastery of materials, processes, mediums and form that the young artist / craftsman that I was had never seen, even at Expo 67, at home. A deployment of incomparable diversity of styles. A fascinating explosion of creativity.

Back in Montreal, I painted Calibre 38.

In British Columbia I had seen mountains on which had grown forests of gigantic millennial trees completely razed. An unnamed sacrilege towards giants, some of whom were there 3000 years ago, long before the Roman Empire. All that remained were scraps of miserable-looking tree stumps. In California, I had witnessed the boundless materialist frenzy of a world celebrating their being at the forefront of contemporary materialist modernity. Both have been the origin of two recurring themes in my work. The singular figure of Christ and the environment. Back home, I painted several paintings in acrylic. One of these paintings on glued canvas represented a strange Jesus Christ standing alongside a large cross refined geometrical cross that I entitled Calibre 38. It is the calibre (9 mm) of ammunition used by the police services. Dressed in a veil or a swirling cape of immaculate white and azure blue, the colours of the Quebec flag, the forehead surrounded by a thorny crown. Impassive, this surprising Jesus Christ held, a gun in his hand. At 23, I could not quite understand what I had spontaneously painted. Perhaps it was the loss of the founding values of Quebec? The Christ who had been at the forefront of his time who could not bear our backwardness in our time? Was this the image of the rejection of materialism from our world? Should he, like a few centuries ago — which had earned him his crucifixion — chase the thieves from the temple anew?

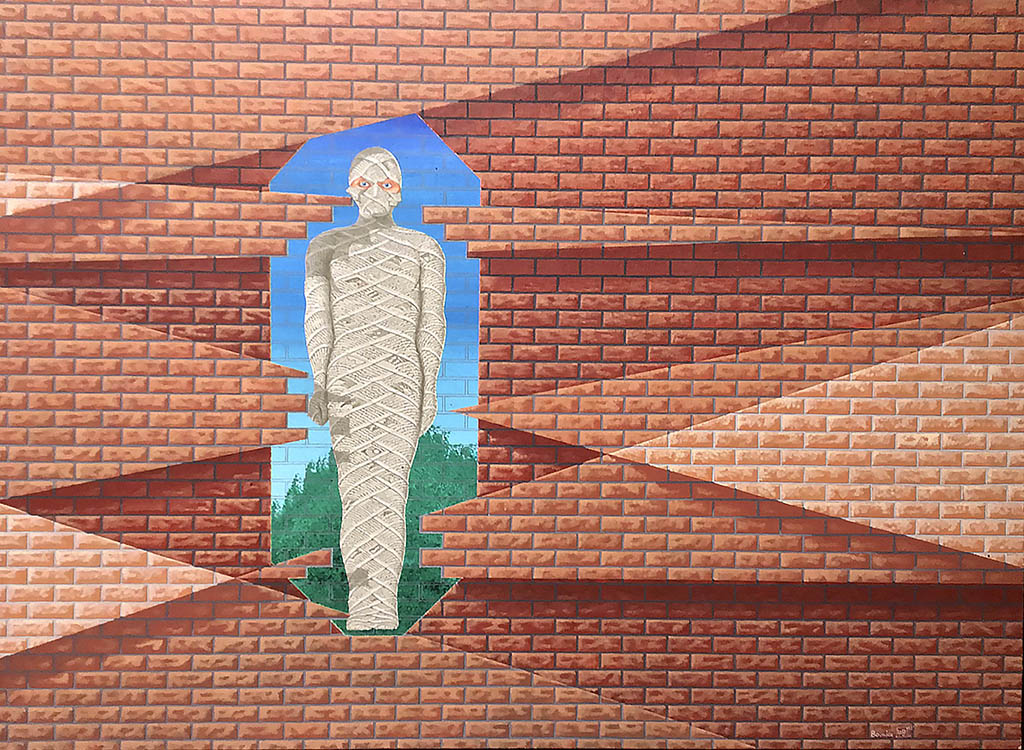

Momie en brique ( walled in brick mummy)

In 1982, at the age of 32, I was still — preferring to indulge in art brut rather than confining myself to the academic — a self-taught artist. It was only at the age of forty that I consented to enroll in university and at the age of 46 obtained a master’s degree in art education.

My family and I lived on rue Aylwin, in the Hochelaga District, a stone’s throw from the current famous pediatric clinic of Doctor Julien, the district to which, when I was 10 years old, we had been forcibly moved by the municipal authorities.

What I read in the newspapers, what was transmitted by the media displeased me to the highest degree. Nothing they claimed matched the human character of our neighbourhood.

I made a work of it by painting a self-portrait that I called Momie en brique ( walled in brick mummy). Living in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve had the looks of a Greek tragedy. There was a bit of the ancient Jesus Christ in the average citizen of Hochelaga-Maisonneuve.

I painted this character by tracing the measurements that were mine at that time. It was a bit of a self-portrait. A vision that would be subject to different treatments over the years. A living mummy with a wrathful gaze. Eyes unobstructed and right fist clenched, the whole body standing straight wrapped by solid strips composed of newspapers that claimed to know us better than ourselves.

A straitjacket made of ink and paper.

We were, and still are – which I still do not understand – since we religiously follow all the rules imposed on us from early school, this needs to want to put ourselves in ever-shrinking confinement cages, while the distressful social reality was already plainly doing the job.

Behind the motionless figure, without being quite still, is a view of the azure of the sky and the foliage of a forest landscape. A remnant of resplendent nature which is also internal to the character.

A wall made of bricks with parts made of aggressive sharp spikes surrounds the character. A gradual walling in which foreshadowed what seems to be forty years later imposing itself ineluctably on our world.

Homumain (humanized man)

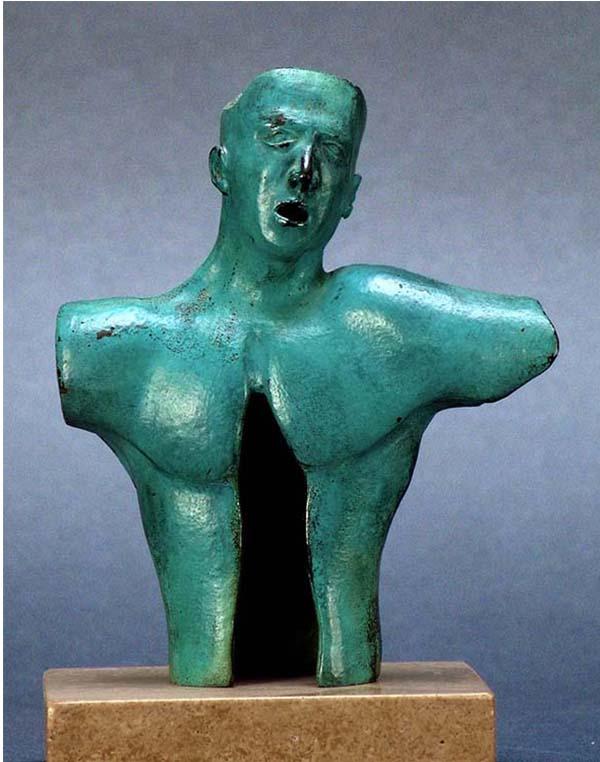

In 1987, the painting of Jesus Christ from 1973 and Momie en brique from 1982 merged into a third work that I titled Homumain.

When the watch movement was designed, the idea of God became the great watchmaker. The steam made it another idea of the world. The atom made him different again. This is no different with the computer, which an author named Pierre Lévy called a universe machine. Especially AI which, converted to digital technologies, takes refuge under the skirts of artificial intelligence.

The rational mind — Iain Mc Gilchrist, English psychiatrist and specialist in neuroimaging, would say the left hemisphere, clumsily clumsy — is such that it sees, without really understanding it, the world as if examining it narrow by waving a narrow beam of a flashlight. Through the keyhole, or the shadows of Plato’s famous grotto.

A few ideas, a few objects more than all the others always seem to him to hold the keys that open all the doors. The rational mind seems binary, either open or closed, always linear and sequential.

At that time, I saw images of so-called ferrite memories. They consisted of thin metal wires at the intersection of which were stuck tiny ferrite cores (ring shapes) that could be electrically charged.

I then clearly imagined the character of Homumain seized by his humanity, at the intersection of two axes that pierced him from side to side. Celebrated when it comes to life, nature, perhaps even the universe, unfortunately, it seems to us, immolated when it comes to the human world since its history has been written.

From left to right, the horizontal axis pierces the suspended body of Homumain, passing through the outstretched arms at the height of the scapular. The horizontal axis represented the horizon of life beyond which one could not see. The vertical axis of a spiritual nature passed through his indented torso and the top of his skull wide open upwards, which must exist since we are rather than not without knowing how and why.

In 1987 it still seemed possible to idealize the human, to place humanity at the crossroads between dark materiality and sublime celestial elevation.

The making of Homumain

During its production, the work comes to life, its history becomes clearer, its character is strengthened. Protagoras said of man that he was the measure of all things in heaven and on earth. Should we add, for the human mind? Marx was a firm believer in the class struggle – social in fact, pitting a few rich individuals against countless poor, a few rulers reigning over the many. Jean-Paul Sartres said that hell is other people. What others? Taunting questions for a human world that is too often profoundly nagging.

Which side do we think the citizens of Hochelaga-Maisonneuve are on? Where do most humans lie? What can the artist who is impregnated with it every day of his decades-long life do with it?

During the 80s decade, I practically only made cast in bronze artworks. The bronze of art coming to us from a long tradition dating back to the Bronze Age, the development of our civilization, the permanence of chosen artworks. In fact, the artist does not sculpt bronze. At least not directly. Bronze sculptures are always made in a material other than bronze. They are either made of wood, plaster or many other materials rigid enough to make a mould allowing them to be cast in foundry sand or to make a reproduction in wax.

The wax reproduction or wax sculpture is then, using the lost wax process, cast in metal.

Homumain was sculpted in wax by hand. Under the effect of the heat of the hands and the pressure of the fingers, the brown wax becomes easily malleable. It is a material whose contact is very organic, quite easy to use and inexpensive, conducive to spontaneous creation, which I like a lot.

Homumain wax was then cast in bronze in a foundry that once participated in the realization of the work and sadly had to close its doors a few years ago.

Coming out of the foundry, a bronze sculpture has a very raw, rough appearance, full of flaws. I corrected the imperfections and finished it myself up to the patina and the mounting on a base.

The roughing, brushing and polishing done, the first layer of patina based on mordant liver of sulfur takes on shades ranging from brown to black. This first layer of patina is followed by the brushed application of copper nitrate, which makes it possible to quickly obtain the beautiful verdigris of the roofs.

It is a process that involves certain health risks since the copper oxide applied to the lightly heated bronze with a torch is suspended in extremely corrosive nitric acid.

In the end I applied two layers of wax on the sculpture that I had put to heat in the sun.

All these details made of techniques, chemistry, gestures and procedures are an integral part of the work. A kind of ritual. It is almost alchemy that transforms society, the human world, the artist as much as the material he shapes. They are part of the work, of its personality, of its character, of the relationship that the artist has with the world of work. Of his understanding of the whole.

Even made of bronze, the sculpture retains traces of its contact with the hands of the artist. Sometimes the fingerprints of the artist remain engraved in the bronze. A warm closeness, of intimacy even with matter.

The body of the work is a kind of embodiment of the artist self, of the artist’s sensitivity and of the world around him. The work grows between the artist’s fingers like a flower or a tree emerging from the fertile ground.

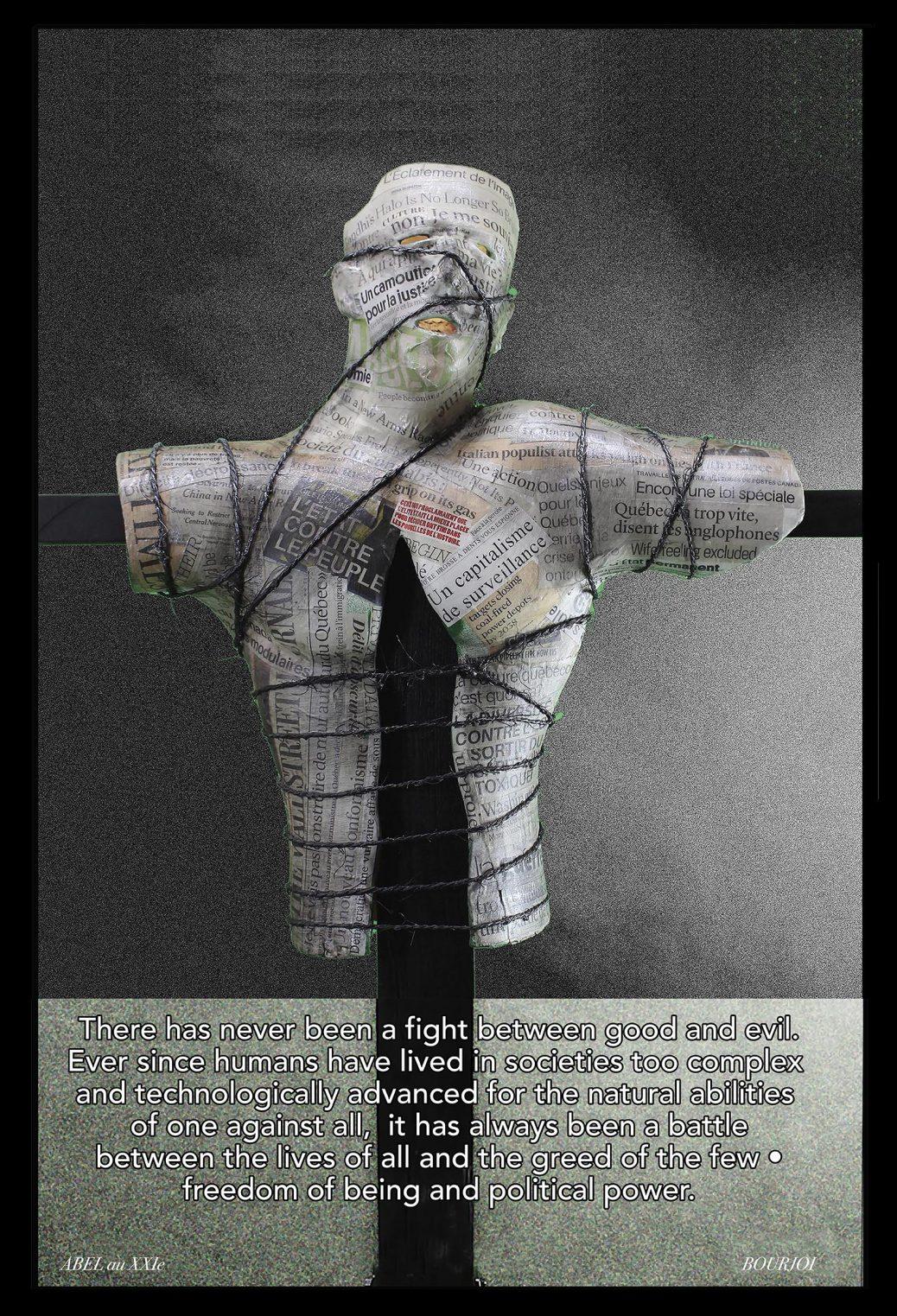

Abel

Art can only be a search for what constitutes our humanity, a haunting search for what has been human for the past 30,000 years. Through the works we perceive the state of the condition, of human nature in the long, medium and short term, sometimes also the future that this portends.

Between the making of Homumain and Abel, 35 years passed. Thirty-five years that turned out to be progressing at the antipodes of what the 1960s presaged. Was on the way to progressing for the better.

Alas, during these 35 years, everything that should have served for progress has served to wage war, to militarize the police forces, to amplify the hold of the media and society of consumerist indebtedness on the minds. To materially exploit the environment and all living things. Who would dare to say otherwise?

The scarier the world was, the more we talked about quality of life, the less there was. The more technological and material means there were to get by, the less we succeeded.

In ancient Egypt, stone pyramids were built to serve the eternal concerns of a few. In the 21st century, billions of us are building an immeasurable human pyramid for a few who could all fit together in a small feudal forum.

Twenty centuries ago, when a subject (citizen) displeased the power at be, serving as an example for all others, he was hung to agonize painfully and finally die, on a cross made of wood erected on the public square.

In the 21st century, it is no longer done to nail humans to pieces of wood, in the public square. In the 21st century, the wood of humanity’s immolation has changed places, it’s not made any more, it grows from within.

A perpetual fight between the multitude who only aspire to live and a few who only seek to possess everything.

Assaulted from all sides, especially from the inside, the human no longer keeps anything inside him and loses his bearings. He can no longer tell the difference between what constitutes the self and what is only agitation outside of itself. Whether ideas, narratives, material or immaterial inoculations, the inside is just another outside.

It is no longer the seat of an inner garden of free growth. Exposed to everything that makes the outside as if it were of the same nature as the inside, the contemporary citizen is no more than a victim, the body between open, frozen with doubts, anxieties, denials and or cowardice.

It would seem that the followers of materialism, this same materialism which has already been represented in the guise of the golden calf, are unable to evolve with the rest of humanity.

The more technological and scientific resources of humanity increase, the more they monopolize them, the less they leave to humanity.

Centuries of humanistic civilization had no effect on their character. Centuries of technological progress still serve them only to get the best out of everyone until everything and everyone is exhausted.

They behave in the 21st century as they did when Solon, the Athenian laid the foundations of democracy in the 6th century BC.

The multitude does not dare to believe that very soon by the will of one man, even if it is deprived of everything, it will have as always to make it its happiness.

The brutality of the human condition of centuries ago is no more. It has changed into a much more subtle condition to the point of being unrecognizable even in the eyes of the multitude who, as in all ages, have nothing to do with pyramids of gold or stone and only seek to live in freedom as nature has done for millions of years.

This nature that transhumanists, who are once again only a few, despise more than anything.

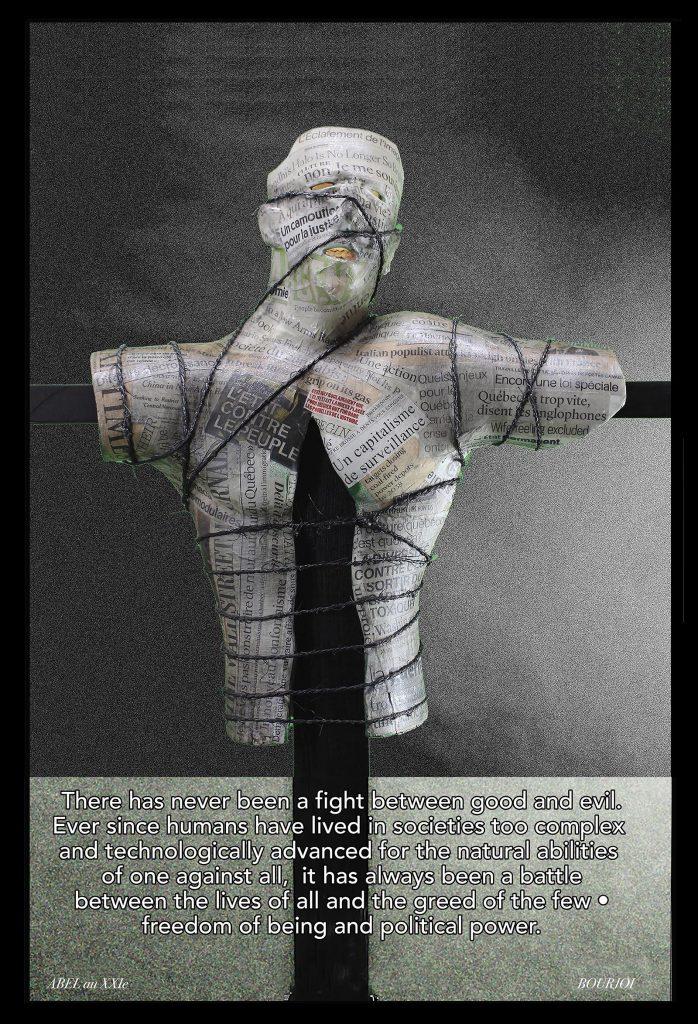

Abel, hence the title of the work, symbolizes the first assassination at the beginning of civilization. The one who only wanted to live who was, however, murdered by the one who only wanted to possess. We are all, Abel, who only want to live peacefully with our family, our children, our friends.

Formally, Abel

The development of computer technologies and their instruments has an important influence on the way of making works of art. As they developed, I never hesitated to use them. Some works cannot avoid borrowing their character from the world of which they are the expression.

I had in the art collection of the original sculpture of Homumain. I had it scanned using a 3D scanner, making it a computerized model. I lost contact with the material while accessing a greater flexibility of realization. The computer file makes it easy to work on its shape and dimensions.

Using a numerically controlled milling machine, a reproduction much larger than the original was carved from blocks of plywood that I had laminated in several layers. It resulted in two wooden shells, one for the front part and the other for the rear part, which were hollowed out and closed, sanded and completely painted, both inside and outside.

Using a numerically controlled milling machine, a reproduction much larger than the original was cut from blocks of plywood that I had laminated in several layers. I obtained two wooden shells, one for the front part and the other for the rear part, which were hollowed out and closed, sanded and completely painted, both inside and outside.

I then fixed the shell of the torso on a wooden structure I made in the shape of a T. The central part is composed of two parts held together using two steel splints reminiscent of a prosthetic system fixed on each side of a bone fracture.

Four steel pieces screwed onto each side of the central piece of wood to make up a support system comprising four supports resting on star-shaped acrylic discs.

Beneath the steel legs structure, two cast-iron dumbbells have been welded together and painted with gold metallic paint. It represented the mass and inertia of the immovable gold present throughout human history. The weights, the mass of inertia coming to us from a history which from one generation to another is constantly repeated itself.

On January 29 and 30, 2019 — I did not foresee that 2020 and beyond would be exponentially worse — I obtained several newspapers from which I cut out a few dozen article titles. I completely covered the sculpture with these newspaper headlines by arranging them randomly and gluing them with painting medium which I then varnished. The painting medium forms a translucent film. In anatomy this is called the superficial fascia covering the muscles under the skin.

Painting is for my sensitivity, a thin skin, a flexible or rigid surface. Sometimes I scarify it to make a scar or an open wound revealing what’s underneath.

Newspaper ink symbolizes tattoo ink on the skin.

I did not choose the newspapers or the titles that were there. I took what was there and cut out the titles that were there. These titles, each more anxiety-provoking than the next, all dealt with problems and realities far removed from the ordinary life of the citizens of my neighbourhood. Even of all Quebecers since 56% are deemed to be more or less illiterate.

I represented the intensity of the tensions and suffering transmitted by the media of all types by tying up, like a leg of ham, the torso of paralyzing anxieties.

The horror came from their number and the extravagance of concerns that had almost no relevance to the ordinary citizen. A way to awaken the atavistic fear of Leviathan and the feeling of helplessness that comes with it.

Thus exposed to all sorts of threats, the body loses all control over itself. The human thus opened no longer knows what is his and what is not, what concerns him and what does not concern him.

The moral appearances of the modern world no longer allowing it, it is no longer done to crucify bodies in the public square. The modern world is content to vilify the masses as if they were the reflection of only one, as if the individual could not grow, learn and understand in the course of a lifetime.

Destroying reputations, depriving of participation in society, depriving many of a life worth living is easier and so much more civilized.

From now on, this is only done from within, only through anguish, countless worries, put together, all aspects of despair.

This Abel is a precursor to a series to come. A diverse series representing a deep desire to exist to simply live as nature intended – despite the worshippers of pyramids – as nature has simply intended for millions of years.

It is impossible to be indifferent to what is being done to the world since we have the words to write history. I worked from one end of Quebec to the other. I have never in seventy-two years of life, met a single person who would have made the world, what those who have the power have made of it convinced that they are that there can be no other ways.

I believe there are other ways of making the world. I do it every day. I have known thousands of women and men, I meet them every day, who experience the world differently. Better, much better than what is offered to us.

Abel is the emissary of the distress that would have no place if our world ceased to be a world-producing trinkets and beads and really became a world in which to live in all simplicity.

Note :

Poster produced on January 16, 2023, as Oxfam released its annual report on the horrific rise in social inequality across the planet for all humanity.