Since I started writing for QuartierHochelaga, our dear collaborative media outlet, readers and friends have commented on my writing, and on occasion, they have asked me about the fear I should feel when it comes to criticizing conformist thinking.

While I can’t say that I never think about it, since everyone, myself included, noticed that the Charbonneau commission limited itself, so to speak, to blaming a worker for having an authoritative glare, while society denies him the right to exercise any authority. I take it with a grain of salt, however, even though I admit that the idea of eliciting a few reactions, however small, pleases me. Otherwise, why would I have bothered becoming Hochelaga’s artist worker and meaning seeker?

This wasn’t my original intent, as I was a conflicted and timid child who hid his curled-up hand in his sleeve, who candidly and ardently wished to understand our world’s truths as well as the grown-ups and cultured people around me.

As I reached adulthood, my candour disappeared and I began to accept the unique character of my worldview, which was that of a working-class intellectual autodidact, even though I have a master’s in fine arts education, which, contrary to what is expected of so-called populist citizens, comes with the right to question the hum of conformist, ready-made thinking.

Having been born disabled, I am also quite familiar with the effects of marginalization, as I experienced it firsthand for many years, and while it remained very obvious for a long period, over time, except when I was a high school teacher, it became much more inconspicuous and took on many seemingly benign forms.

When a marginal individual becomes self-aware, the conformist unconscious, which can transform them too easily into an invisible victim, can never feel satisfying.

This is why the artist, worker, disabled person and everyone else must write about what concerns them directly. Since they are actually affected, they are the first to understand what society puts them through before society can even come to terms with it. They can only complain or hurl accusations, as everyone complains about everyone else anyway, but rather, as a result of having been articulated, they could finally reach the ears of those who can make a difference, even though there are too few who fit this description, which is not a good sign for democracy.

I didn’t reach these conclusions randomly or by striking a reflective pose on a bench like Rodin’s Thinker. They are the result of having thrown myself into countless life experiences and never having hesitated to learn new skills in several regions across Québec. I also gained a lot from being actively immersed in many lines of work, all while passionately referring to many written works composed by minds far brighter than I will ever be.

This conscious search for meaning brings me to declare that, given the nature of human psychology and its necessarily attendant egocentrism, it takes a disabled person to understand disability, one who has been dominated to understand domination, one who has been sick to understand sickness, one who has been excluded to understand exclusion, as Gustav Eckstein made it abundantly clear in his book The Body Has a Head, which was published in 1969.

According to Eckstein, who was an expert in the field, the brain is a living organ like any other, such as the liver or the heart.

When we believe that our brain is thinking, it is actually coming up with different strategies, ways and tricks to stay alive, whether it is by learning to read or eating with a fork, thinking in Mandarin if the person is born in China or in French if he is born in the Hochelaga neighbourhood. Whatever perpetuates is life, from the brain’s perspective, is all the same.

We should no longer be looking everywhere while resorting to all kinds of fantastical explanations that we have inherited from our ignorant past. Fundamentally, it is a question of learning and the degree to which this learning sticks. Didn’t the Jesuits used to say, several centuries ago, that if you were to give them a five year old child, they could turn him into any kind of man they wanted?

Gears and cogwheels background illustration

Consequently, the dystopian world in which we live could very well be different. If humans recognized themselves in their culture, thinking about it differently would suffice.

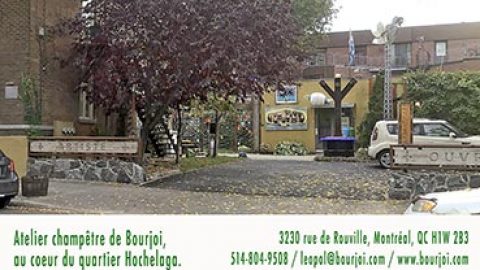

A life story that is as unique as any other life story is a good start. It’s the best I have to offer you and that’s what I’m going to deliver over the course of the pieces that I will be publishing in French every two weeks in the QuartierHochelaga collaborative media forum and in English on my Blog in 2018.

Translated by Remi L. info@bourjoi.com