Pour moi qui ai grandi dans le quartier Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, lorsque j’ai imaginé la sculpture Pourquoi naître ?, en demandant aux citoyens d’y participer collectivement, cela me semblait aller de soi. Une occasion inévitable d’extraire une œuvre d’art de la nature historique de notre cher quartier qui n’attendait, j’en suis toujours convaincu, qu’une occasion pour exprimer ses valeurs historiques.

Pourquoi naître ?pourrait aussi bien être un arbre radieux qui aurait soudainement poussé en pleine maturité au milieu de notre quartier.

C’est en partie pour cela que la sculpture publique Pourquoi naître ? fait office de croix de chemin pour un quartier à la croisée des chemins.

Qualifié dans mon quartier d’artiste-ouvrier, fils d’ouvrière et d’ouvrier, j’ai écrit le court poème suivant pour l’occasion. Il a été taillé à l’emporte-pièce dans l’acier qui compose l’oeuvre:

Pourquoi naître, si ce naît pour vivre ?

Pourquoi le travail, si ce naît pour rester en vie ?

Pourquoi ouvrier, si ce naît pour construire le monde à d’eux ?

Comment vivre, si ce naît ensemble ?

Derrière le texte est installé un luminaire aux couleurs changeantes, représentant le quartier qui se métamorphose de multiples manières. Les valeurs du monde ouvrier que la sculpture représente sont illuminées de l’intérieur.

Tout dans cette sculpture a un sens. L’engrenage et ses 7 rayons représente les 7 jours d’une semaine et ses 52 dents, les 52 semaines d’une année. La base primaire de la sculpture de 52 pouces de diamètre est surmontée d’une deuxième plaque d’acier plus mince de 24 pouces de diamètre représentant les 24 heures d’une journée.

Grâce au savoir-faire d’André Bourgeois, contremaître d’expérience à l’atelier de René Thibault, les poutrelles et la base ont été assemblées à l’aide de rivets traditionnels comme cela se faisait dans le quartier au 19e siècle et au début du 20e siècle.

12 gros rivets d’acier maintiennent les plaques circulaires. Ils représentent les 12 mois de l’année et les 12 heures de l’horloge qui rythment la vie de l’ouvrier.

Afin de représenter les 8 heures de travail d’une journée ainsi que la hauteur des logements des ouvriers, la poutrelle centrale mesure 8 pieds de long en hauteur. Il s’agit aussi de la longueur des 2×4 en bois et des feuilles de gypse servant à la construction des logements, et de bien d’autres choses.

Le chemin de fer est un élément important de notre quartier. Il fallait que la sculpture fasse aussi référence à une traverse de chemin de fer en y intégrant la partie supérieure du X qu’on voit à l’intersection des routes qui le traversent. La forme est également inspirée du symbole de Terre des Hommes, dont nous voyons les îles des rives de notre quartier, et du signe de paix universel retourné sur lui-même de bas en haut.

Ce n’est pas tout.

La sculpture a été fabriquée avec de l’acier Corten, utilisé en architecture et en art pour ses propriétés métallurgiques exceptionnelles. La première oxydation rougeâtre le protège de toute oxydation subséquente et le rend six fois plus résistant aux intempéries que l’acier ordinaire. Cette propriété représente bien le caractère et la très grande résilience du monde ouvrier.

La sculpture est formée de trois poutrelles en acier qui ont été fabriquées plutôt que composées simplement de poutrelles standard en H. Ces poutrelles ont été découpées en bandes dans une seule plaque, assemblées et soudées à la main par un soudeur du nom de Gabriel à l’entreprise de René Thibault, qui œuvre dans notre quartier depuis plus de 40 ans et qui a collaboré de bonne grâce à la fabrication de la sculpture. Le Comité Central du Montréal Métropolitain de la CSN, dont plusieurs membres vivent dans le quartier Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, a également participé au financement de l’oeuvre.

De part et d’autre de la sculpture, en haut des poutrelles, est soudée une paire de gants. Les gants de Joseph symbolisent le travail manuel concret, son élévation et la résistance que démontrent tous les ouvriers malgré les forces de la gravité qui usent et tirent vers le bas. Ce sont des véritables gants d’ouvriers usagés qui ont été reproduits directement en bronze par calcination en faisant usage du procédé dit de cire perdue en coquille de céramique.

Le bronze de l’art nous vient de l’âge du bronze à l’origine de notre civilisation technologique. En faire usage dans une sculpture à caractère ouvrier est une manière de les inscrire dans la longue tradition des hommes et des femmes qui, depuis des temps reculés, construisent pour nous tous le monde matériel sans chercher à le posséder pour eux seuls.

Au sommet de la poutrelle centrale a été fixé très solidement un casque de sécurité en métal que portent les ouvriers sur les chantiers de construction. Il est couvert de feuilles d’or pur du même type que celui utilisé dans les églises du quartier. Cet or en fait un dôme architectural, un couvre-chef de dignité, de valeurs humaines et de noblesse de caractère.

Pourquoi naître ? est une œuvre inhabituelle, une création spontanée, un citoyen culturel créé grâce à l’esprit d’un quartier qui ne craint pas d’ouvrir ses portes à l’avenir.

La sculpture, citoyen culturel Pourquoi Naître? a dû être déménager devant l’atelier de Bourjoi, Artiste ouvrier d’Hochelaga, sur la rue de Rouville le 1er mai 2018 après avoir été expulsé du site où elle était depuis 2015 près de l’église Nativité de la Sainte-Vierge sur la Rue Dézéry.

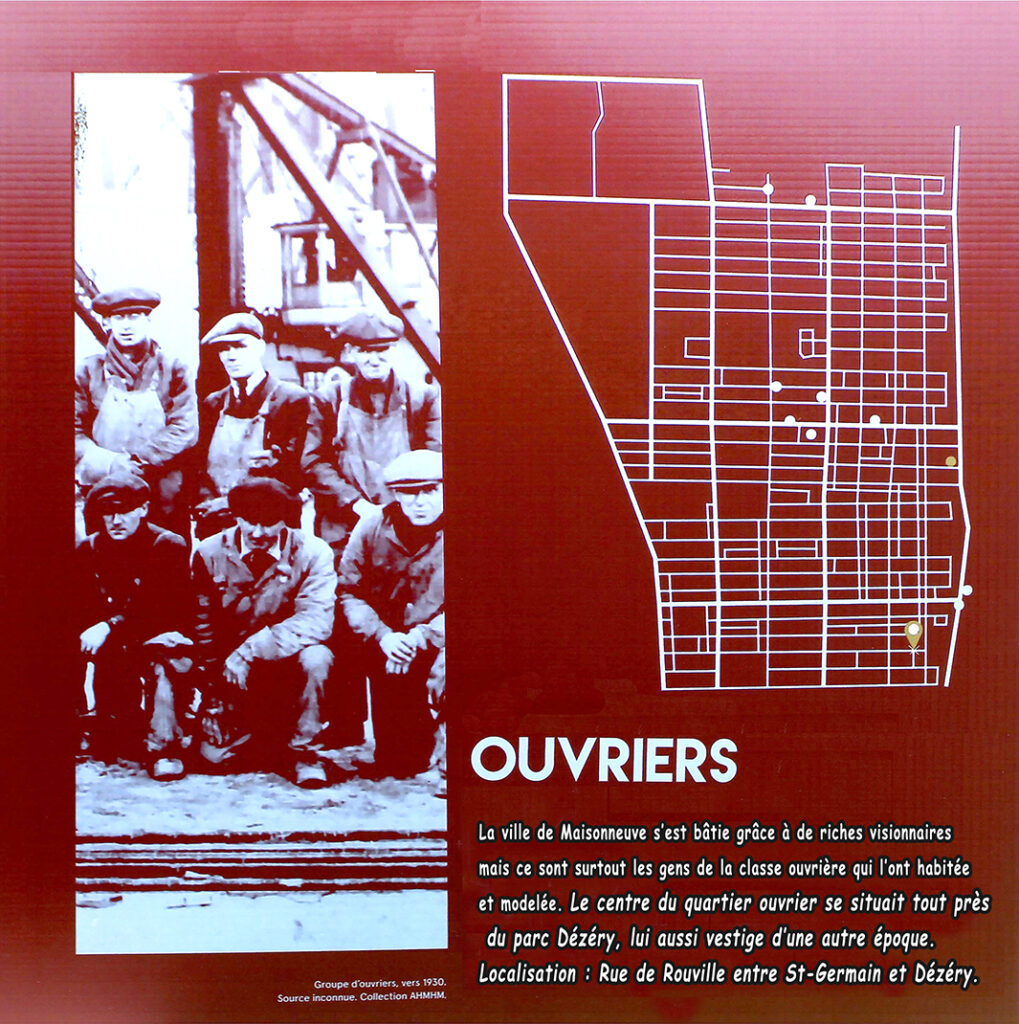

Pourquoi Naître? Le patient vigile, le citoyen culturel témoigne des valeurs historiques du quartier Hochelaga. Depuis le 1er mai 2018 la sculpture, accessible au public, est devant l’atelier de l’artiste sur la rue de Rouville. Bourjoi artiste ouvrier du quartier Hochelaga est toujours prêt à vous recevoir. Le hasard a fait que la résidence et l’atelier de l’artiste soient au même endroit où en 1930, selon l’atelier d’Histoire Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, se situait le coeur du quartier ouvrier sur la rue de Rouville entre les rues Saint-Germain et Dézéry.